Think of primary sources as the raw materials of history. They're the original documents, objects, and first-hand accounts left behind by the people who were actually there. This is your direct line to the past, offering firsthand evidence from a specific moment in time before anyone else has had a chance to interpret it.

What Are Primary Sources and Why Do They Matter

Let's use an analogy. Imagine you want to understand what a famous historical speech was really like. A primary source is like listening to a recording of that speech yourself—hearing the speaker's tone, the crowd's reaction, and the pauses. You get to form your own impressions directly from the event.

A secondary source, in contrast, would be reading a historian's chapter about that speech. It's valuable analysis, for sure, but it’s still filtered through someone else's perspective.

This distinction is what makes real research so powerful. When you work directly with different types of primary sources, you get to step past other people's conclusions and engage with the evidence yourself. You become the historian, the detective, or the scientist, piecing the story together from its most basic components. This hands-on approach builds a much deeper and more nuanced understanding of your topic.

Of course, once you start digging, you'll find a lot of material. Keeping it all straight is essential, and exploring modern approaches to research organization can make a world of difference.

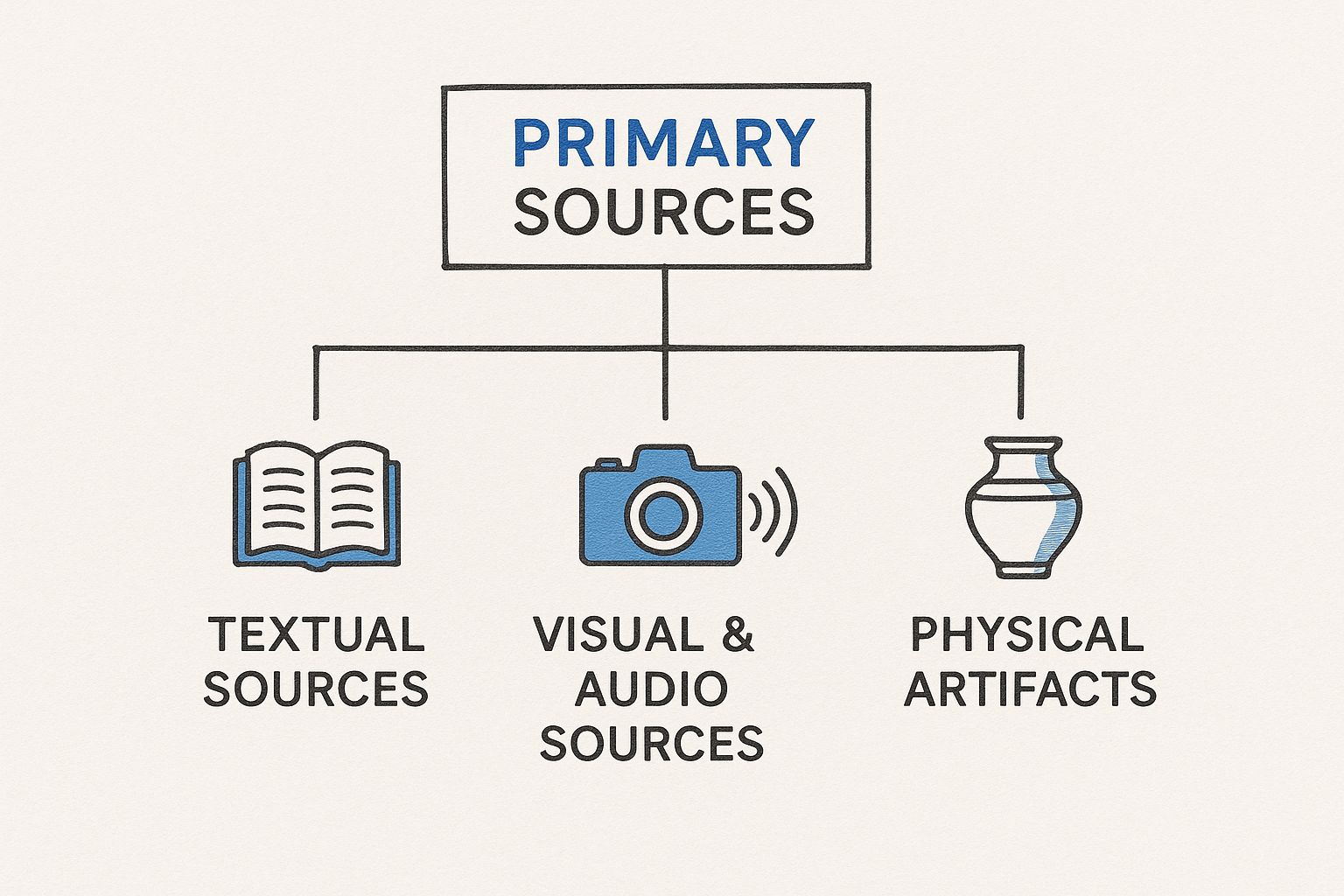

This infographic provides a great overview of the main categories we'll be diving into.

As you can see, "primary source" is a broad term. It branches out into written documents, audio-visual recordings, and even physical objects, with each type offering its own unique window into the past.

Written and Published Materials

When most of us picture a primary source, we probably think of things like old letters, dusty diaries, or yellowed newspapers. It's a natural starting point, as these written documents are often the most direct and powerful way to connect with the past. They give us a front-row seat to private thoughts and public conversations from another time.

Personal documents—think diaries, letters, or journals—offer an incredibly intimate and unfiltered view. Imagine reading a soldier's letter sent home from the trenches; it reveals the raw fear and day-to-day grind of war in a way no official military report ever could. These sources are all about the human side of history, packed with individual emotion and, of course, personal bias.

On the other hand, you have published materials like newspapers and magazines. These capture the public pulse, showing us what an entire society was thinking and talking about as events unfolded. They’re a snapshot of the headlines, cultural obsessions, and collective mood of a particular era.

The Public Story in Print

Newspapers are goldmines for understanding how major events were seen in real-time. Take the 1918 influenza pandemic, for example. Newspapers were the main source of information, tracking infection rates and public health advice as the crisis unfolded. They documented an event that infected an estimated 500 million people and tragically led to somewhere between 20 and 50 million deaths worldwide. Thanks to digital archives, these incredible records are now at our fingertips.

The British Newspaper Archive is a fantastic example of the sheer scale of these collections.

As you can see, this archive alone contains millions of pages that have been digitized from centuries of print, turning what was once a physical search into a simple keyword search.

One of the most important skills a researcher can develop is learning to compare these different written sources. Placing a personal diary entry next to a newspaper article from the very same day can expose a stunning gap between private feelings and the public story.

This kind of cross-referencing is what helps build a truly nuanced and critical picture of the past. It's a similar skill to one you'd use when evaluating modern research; if you're curious about that, our guide on finding a peer-reviewed articles example can show you what to look for in scholarly writing.

Understanding Official Records and Legal Documents

While personal documents give you a close-up, ground-level view of the past, official records offer the blueprint from above. These are the formal, authoritative documents a society uses to run itself, making them one of the most powerful types of primary source for anyone studying law, history, or social structures.

They might seem a bit dry on the surface—think government reports, laws, court cases, treaties, or census data. But dive in, and you’ll find incredible stories. A simple court transcript can reveal fascinating details about the social norms of an era, while a piece of legislation shows you exactly what a government cared about (and what it didn't).

A Window into How Society Works

These documents are the bedrock for understanding how a nation functions. Government papers and official records are the key to tracking policy decisions and seeing how things were managed day-to-day.

The scale of this material is staggering. The U.S. National Archives, for instance, holds an incredible 13.5 billion pages of text and 44 million photographs, including foundational documents like the Constitution. You can even explore a huge collection of these historical world records and documents to see for yourself.

Census data is another goldmine, painting a broad picture of how populations have changed over time.

A great example is the 1850 U.S. Census. It was the first time every single person in a household was recorded by name, giving us a rich snapshot of the lives—occupations, literacy, and origins—of over 23 million people.

How to Track Them Down

Finding these documents is easier than you might think, as many have been digitized and put online. Your best bet is to start with national archives, government websites, or university databases.

When you're searching, be specific. Instead of a general query, try using precise terms like:

- "parliamentary debates"

- "census records"

- "supreme court decisions"

Combine these with a specific year, decade, or location. This targeted approach will help you find the exact blueprints you need to reconstruct the past.

Finding Clues in Personal Papers and Manuscripts

While official records give us the public version of history, it's the unpublished personal papers and manuscripts that tell the private story. These materials—think letters, diaries, speeches, and personal notes—provide a raw, unfiltered look into the lives of individuals. They are the human side of the story, capturing the motivations, emotions, and relationships that often get lost in other sources.

Imagine reading a series of letters exchanged between two people during a major historical event. You're not just getting the facts; you're seeing their emotional journey, their daily anxieties, and what was truly at stake for them. These documents help you connect with the past on a deeply personal level, turning historical figures into real, relatable people.

The Power of Personal Correspondence

Letters are an especially potent type of primary source. They offer intimate glimpses into the culture and context of a specific time. For example, the U.S. Library of Congress holds over 70 million manuscripts, which includes massive collections of letters from figures like Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson, alongside correspondence from everyday citizens.

Digitized collections are also making this easier than ever. Archives like the Early Modern Letters Online database contain over 130,000 letters from the years 1500-1800, giving today's researchers a direct line into the social networks and cultural currents of the past. You can learn more about how libraries preserve these incredible records and the methods for accessing library archives.

Working with these materials definitely has its challenges, like deciphering old handwriting or getting the hang of dated language. But the reward is immense: you get to hear directly from the past, in the author's own words.

You'll typically find these invaluable collections tucked away in university archives, special libraries, and historical societies. Finding them is your first step toward uncovering the private stories that truly bring history to life. The effort it takes to track down and interpret these papers is almost always worth the unique insights they offer.

Interpreting Visual and Audio Sources

Primary sources aren't always something you read. Sometimes, you see them or hear them. These visual and audio materials—think photographs, films, political cartoons, and old radio broadcasts—can capture a moment's emotion and atmosphere in a way text just can't.

They offer a direct, sensory connection to the past, letting us experience events as they originally looked and sounded.

Analyzing these types of primary sources demands a different kind of detective work. You have to learn to "read" images and listen between the lines of a recording. For spoken sources like interviews or oral histories, using tools for accurate AI audio to text transcription can be a game-changer, making the analysis much easier.

Reading Between the Frames

With any visual or audio source, context is king. A government-issued photograph of a protest, for instance, will tell a completely different story than a candid shot snapped by an activist in the crowd. One might project order and control, while the other captures the raw, chaotic energy of the moment.

To get the full picture, you have to ask the right questions:

- Who created this? Think about the photographer, filmmaker, or broadcaster. What was their point of view or potential bias?

- Who was the intended audience? Was this a private home movie or a national news broadcast?

- What is left out? The way a photo is framed or a film is edited always leaves something out. What aren't you seeing or hearing?

These non-textual sources are essential tools for any modern researcher. They provide layers of meaning that words alone cannot convey, from the tone of a speaker's voice in an old radio broadcast to the subtle body language captured in a silent film.

By looking and listening closely, you can uncover powerful narratives hidden in plain sight. This makes your research richer and more authentic. You can often find these materials tucked away in museum collections, national archives, and university special collections.

Analyzing Artifacts as Physical Evidence

So far, we’ve covered sources you can read or listen to. But what about the things you can touch? This is where artifacts come in—the tangible, physical objects that past cultures left behind.

Artifacts are powerful primary sources because they are the real deal. They are the tools people used, the clothes they wore, and the pottery they ate from. Every object, whether it's a simple arrowhead or an ornate piece of furniture, is a direct window into daily life, technology, and social values.

You don’t have to be a professional archaeologist to analyze an object. When you encounter an artifact, think of yourself as a detective trying to make it "speak." Your job is to read its physical clues to understand its story.

How to Interpret Material Culture

Analyzing artifacts is all about asking the right questions. It’s a bit like historical detective work, where the object itself holds the evidence.

To get started, consider these key questions:

- What is it made of? The materials tell you what resources were available and what level of technology people had.

- How was it made? Look for tool marks or imperfections. Was it carefully crafted by hand or churned out by a machine?

- What was its purpose? Was this a practical, everyday tool? A ceremonial item? Or something purely for decoration?

By answering these questions, you start to piece together a narrative. A shard of Roman glass, for example, doesn't just tell you about glassmaking; it can reveal trade routes, economic status, and even artistic preferences of the time.

Museums and historical societies are treasure troves for this kind of research. But you can also find artifacts in antique shops or even your own attic. They are the physical remnants of the past, just waiting for a curious mind to uncover the stories they hold.

Common Questions About Primary Sources

Even after you get a feel for the different kinds of primary sources, a few key questions always seem to surface. Nailing down these fundamentals is the secret to working with historical evidence confidently and, more importantly, effectively. Think of this as your quick-start guide to solving the most common puzzles you'll encounter.

Getting these answers straight will clarify how you should approach primary evidence in your own work.

What’s the Main Difference Between a Primary and Secondary Source?

The real difference boils down to two things: timing and perspective. A primary source is a firsthand account—the raw material from the time period you're studying. It was often created by someone who was right there, in the middle of the action. We're talking about a soldier's letter home from the front, a photograph of a protest, or an ancient piece of pottery.

A secondary source, on the other hand, is a step removed. It’s someone else analyzing, interpreting, or summarizing those primary sources long after the fact. Textbooks, biographies, and scholarly articles that review other people's research are all classic examples.

The best way to think about it is like this: a primary source is the raw ingredient picked straight from the garden. A secondary source is the finished meal a chef cooked using those ingredients. One is the evidence itself; the other is an interpretation of that evidence.

Can a Source Be Both Primary and Secondary?

Yes, and this is a crucial concept to grasp. What a source is depends entirely on what you're asking. Your research question is what truly defines a source's role.

Take a high school history textbook from the 1950s. If you’re studying the Civil War, that textbook is a secondary source because it’s just summarizing events. But what if your research project is about how American teenagers were taught about patriotism during the Cold War? Suddenly, that same textbook becomes a primary source. It offers direct, unfiltered evidence for your specific topic.

How Do I Know if a Primary Source Is Reliable?

Here’s the thing: no primary source is 100% objective. Every single one has a point of view. To figure out if you can trust it, you have to put on your detective hat and investigate where it came from.

Always ask yourself a few critical questions:

- Who made this and why? What was their motivation? Did they have an agenda?

- When was it created? Right in the heat of the moment, or years later when memories might have faded or changed?

- Who was this for? A private diary entry is going to be far different from a public speech delivered to rally support for a cause.

The single best practice is to never, ever rely on just one source. You have to corroborate what you find by checking it against other primary sources from the same period. This is how you start to build a richer, more nuanced picture. As your source list grows, the importance of a reference manager becomes crystal clear for keeping everything straight.

*At Eagle Cite, we build tools to help you manage your research materials efficiently. Our AI-powered citation manager helps you organize sources, find key information with natural language search, and spend more time on analysis. Start your free trial at https://eaglecite.com.