At its core, the peer review process is a quality control system for academic work. Before a research paper sees the light of day in a scholarly journal, it first has to pass the scrutiny of other experts—or "peers"—in the same field.

Think of it as a high-stakes audition. Only the most methodologically sound, credible, and significant research gets to make it to the main stage of publication.

The Bedrock of Scholarly Credibility

Peer review is the essential mechanism that upholds the integrity of academic and scientific research. It acts as a filter, working to prevent flawed, inaccurate, or unsubstantiated claims from becoming part of the accepted body of knowledge.

When you read a study in a reputable journal, you can be confident it has survived this rigorous evaluation. This system doesn't rely on a single gatekeeper but on a collective of qualified experts who volunteer their time. To get a better sense of this dynamic, it’s useful to grasp the idea of understanding what a 'community of practice' entails, as this is the collaborative environment where authors and reviewers operate.

Why This Process Matters

You really can't overstate the importance of this system. It serves several critical functions that benefit not just the scientific community but also the public, who ultimately rely on these findings.

To put it simply, peer review is designed to achieve a few essential goals. The table below breaks down its core functions.

Core Functions of Peer Review

| Component | Primary Goal |

|---|---|

| Validation | To confirm that the research methods are sound and the author's conclusions are logical and supported by the data. |

| Quality Improvement | To provide constructive feedback that helps authors refine arguments, clarify explanations, and correct errors before the work is finalized. |

| Originality Check | To help verify that the work contributes something new, valuable, and significant to the existing body of knowledge in the field. |

The scale of this effort is genuinely massive. In 2020 alone, researchers around the world volunteered an estimated 100 million hours to review papers. This statistic really underscores the critical role this system plays in the world of scholarly publishing.

By subjecting new findings to independent expert assessment, the peer review process ensures that published work meets the accepted standards of a discipline. It is the primary method for maintaining scientific credibility and weeding out pseudoscience.

Getting familiar with this framework is key for anyone who needs to engage with academic literature. The final output of this intense evaluation is what you see in journals. For a clearer picture, take a look at a peer-reviewed articles example to see the level of quality this process produces.

How Peer Review Evolved Over Time

To really understand peer review today, we have to look at where it came from. The concept didn't just appear out of thin air; it slowly grew from informal chats among colleagues in 17th-century scientific societies. Back then, a "review" was often just a simple letter exchanged between a few trusted friends.

Think about a world of handwritten notes and mail that took weeks to arrive. The editor of an early scientific journal might pass a new manuscript to a respected peer for a quick opinion. This whole system ran on personal reputation and trust within very small, elite circles of scholars. There were no formal guidelines or anonymous reviewers—just the word of a known expert.

This casual approach worked for a while, but as the world of research got bigger, its cracks started to show. It was easy for favoritism, personal rivalries, and biases to dictate whose work was published and whose was buried. A more objective system was desperately needed to manage the growing flood of global research.

The Shift to a Formal System

The mid-20th century was the real turning point. The structured, often anonymous process we're familiar with now started to take shape, born from the need for a more rigorous and fair way to check quality.

The formal peer review system we know today really came into its own around the 1950s. Before the 1970s, getting feedback was often an informal process handled by a tight-knit group of scientists. The push for a wider, anonymized system gained momentum through the 1990s as a way to improve fairness and reduce bias by bringing in multiple anonymous experts. This gradual shift set the foundation for the systematic quality control that is now at the heart of academic publishing. You can dive deeper into this historical perspective on peer review to see exactly how these changes unfolded.

This transition from a system of personal trust to one of objective scrutiny was crucial. The goal was to make sure a manuscript's quality—not the author's reputation or connections—was the only thing that mattered for publication.

This history explains a lot about today's practices and ongoing debates. While digital tools have sped things up, the core principles established during this formalization period are still with us. It shows that peer review isn't a rigid set of rules but a process that's always evolving to protect the integrity of human knowledge.

Comparing Different Peer Review Models

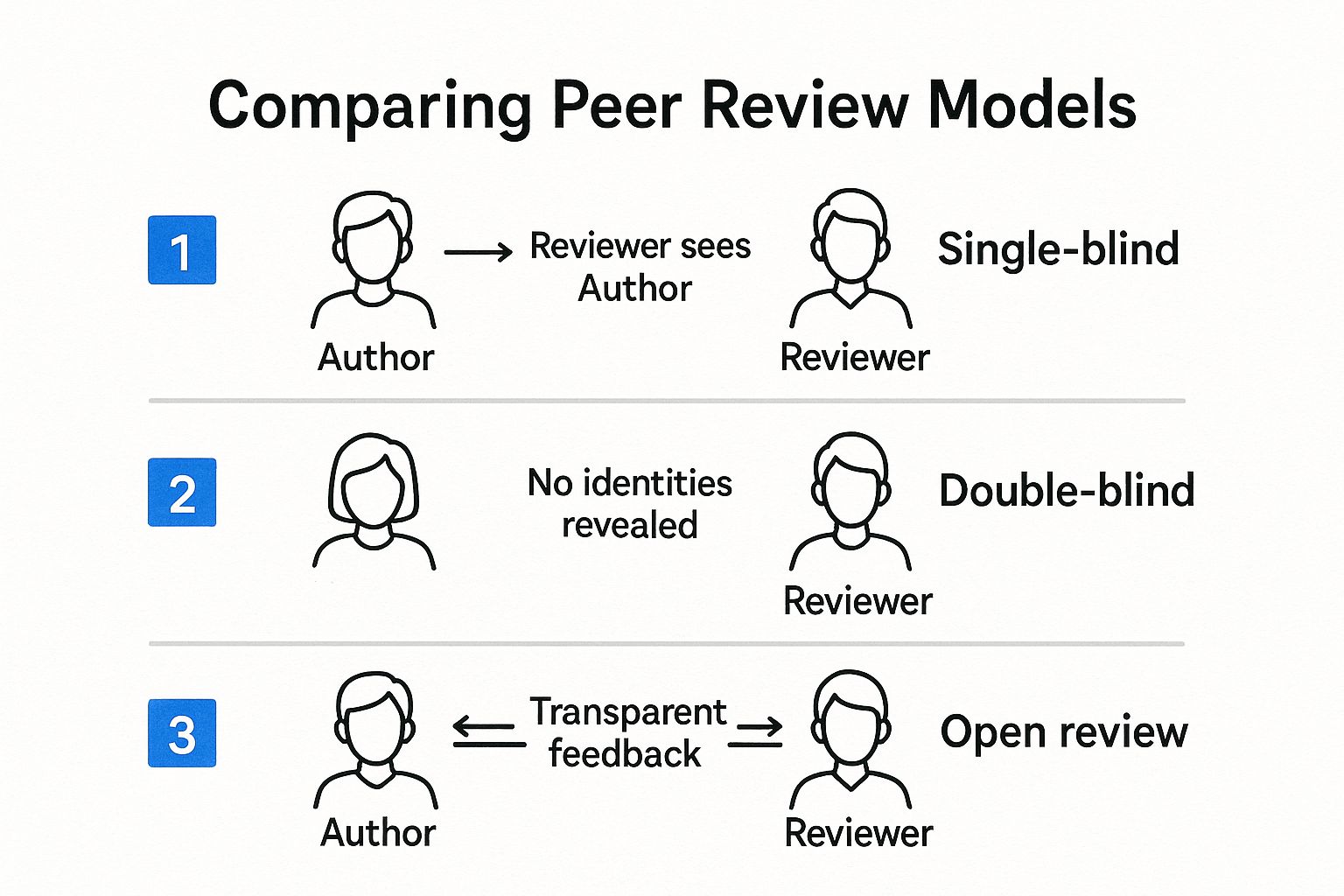

When you hear the term "peer review," it’s easy to think of it as a single, rigid system. But that’s not really the case. It’s more of an umbrella term for several different approaches, each with its own philosophy on anonymity and transparency. The specific model a journal uses fundamentally shapes the entire experience, from how candid a reviewer feels they can be to the potential for bias to creep in.

Figuring out these differences is crucial to understanding how the peer review process actually works in the real world. A journal's choice of model says a lot about its priorities—whether it’s aiming for pure, unbiased evaluation, encouraging open dialogue, or fostering a sense of accountability in the academic community.

The infographic below gives a great visual breakdown of how the three most common models handle who knows who.

As you can see, the flow of information and anonymity directly impacts the power dynamics at play.

Single-Blind Review

The classic. In a single-blind review, the reviewers are anonymous, but the author isn't. The reviewers know exactly whose work they’re reading. This has long been the standard model in many scientific fields.

The thinking behind it is simple: anonymity frees up the reviewer to give brutally honest feedback. They can point out major flaws or even recommend a flat-out rejection without worrying about backlash from a big name in their field.

But there’s a catch. This model is susceptible to bias. A reviewer might be swayed, even subconsciously, by the author's reputation, their fancy institution, or even their gender or nationality. This can lead to a "halo effect" for established researchers and an unfairly critical eye on work from newcomers.

Double-Blind Review

To combat the bias problem, many journals have moved to a double-blind model. In this setup, it's a two-way street—the author doesn't know who the reviewers are, and the reviewers don't know who the author is. The manuscript is stripped of all identifying information before it goes out.

The entire point of a double-blind review is to make the manuscript the star of the show. It’s an attempt to force reviewers to focus solely on the quality of the work itself—the research, the argument, the data—and forget about the author's pedigree.

Of course, it's not a perfect system. In highly specialized fields, a reviewer can often make an educated guess about the author's identity based on the research topic, self-citations, or a unique methodology. The veil isn't always completely opaque.

Open Peer Review

The newcomer on the block is open peer review, and it flips the whole concept of anonymity on its head. Here, transparency is king. Not only are the identities of the author and reviewers known to each other, but often the review reports themselves, along with the author’s responses, are published right alongside the final article for anyone to see.

- Accountability: When reviewers know their name is attached to their comments, they tend to be more constructive and civil. It discourages lazy or overly harsh critiques.

- Credit: Reviewing is hard, often unpaid work. This model gives reviewers public credit for their intellectual contribution.

- Dialogue: It reframes the process from a private judgment to a public, collaborative conversation aimed at making the science better.

These models aren't just theoretical, either; they have real-world effects. An analysis of 24 different randomized trials found that blinding reviewers to author identities did slightly improve the quality of reviews, though it also tended to slow things down. Interestingly, open peer review was linked to lower rejection rates, suggesting it fosters a more cooperative spirit. You can dig deeper into the history and impact of different review models to see how these debates have evolved over time.

To make it even clearer, let's break down the core differences in a side-by-side comparison.

Peer Review Models at a Glance

This table offers a quick look at how single-blind, double-blind, and open peer review stack up against each other, highlighting their key features, main benefits, and potential drawbacks.

| Review Model | Key Feature | Primary Advantage | Main Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Blind | Reviewers are anonymous; author's identity is known. | Encourages candid reviewer feedback without fear. | High potential for bias based on author's reputation. |

| Double-Blind | Both author and reviewer identities are concealed from each other. | Reduces bias by focusing on the manuscript's merit. | Anonymity can be difficult to maintain in niche fields. |

| Open | All identities are known; review reports are often published. | Promotes accountability, transparency, and collaboration. | Reviewers may be less critical for fear of professional conflict. |

Each model represents a different trade-off between protecting against bias, encouraging honesty, and fostering a collaborative academic culture. The "best" model is still a subject of hot debate, and the choice often depends on the specific goals and culture of a journal or field.

The Peer Review Journey: From Submission to Decision

Knowing the theory behind peer review is one thing, but actually seeing a manuscript's path from an author's laptop to a final decision really brings it to life. Think of it as an academic gauntlet. Every paper has to prove its mettle at each stage, facing different gatekeepers and potential outcomes along the way.

This entire workflow is built to meticulously filter and strengthen research. It all kicks off the second a researcher hits "submit" and doesn't truly end until the journal editor makes that final call. Let's walk through what really happens on this journey.

Stage 1: The Initial Submission and Editorial Triage

The adventure begins when an author uploads their manuscript to a journal's online portal. This is more than just attaching a file; it involves filling out metadata, confirming author details, and declaring that the work is original and not being considered anywhere else. A strong paper starts with a solid foundation, and you can learn more about crafting a compelling manuscript by exploring our guide on how to write an introduction to a research paper.

But the paper doesn't go straight to outside experts. First, it lands on the desk of the journal's editorial staff for an initial screening—a critical first checkpoint.

- Format Check: Does the paper follow the journal's specific rules for word count, citation style, and structure?

- Scope Check: Is the research topic a good fit for the journal's focus and readership? A brilliant marine biology paper, for instance, has no place in an astrophysics journal.

- Basic Quality Check: Is the writing clear? Does it look like a serious scholarly effort?

This initial "desk review" is a crucial filter that weeds out submissions that are obviously a poor fit, saving everyone a ton of time. A surprising number of papers, sometimes 15-20%, get rejected right here. This is known as a desk reject.

Stage 2: Finding the Right Editor and Reviewers

If a manuscript makes it past that first hurdle, it's assigned to a subject editor—an academic who is an expert in that specific field. This editor gives the paper a closer read to decide if it's solid enough to send out for formal peer review.

Next comes the editor's most challenging job: finding and inviting the right peer reviewers. It's much harder than it sounds. They need to pinpoint experts with the precise knowledge needed, who are actually available and, crucially, have no conflicts of interest with the authors. The goal is to secure two to three independent reviewers to get a well-rounded set of opinions.

Stage 3: The In-Depth Review

This is the real heart of the peer review process. The invited experts receive the manuscript (which may be anonymized, depending on the review model) and are asked to deliver a thorough critique. They don't just give a thumbs-up or thumbs-down; they dig deep, evaluating the work against rigorous academic standards.

During this phase, reviewers act as critical friends. Their job is to rigorously test the research's foundations, question its assumptions, and offer constructive feedback to strengthen the final paper.

Reviewers usually write up detailed comments for the author and also provide a confidential recommendation to the editor. They're looking at everything: the study's originality, the soundness of its methods, the validity of its conclusions, and its overall contribution to the field.

Stage 4: The Editor's Decision and Author Revisions

Once all the reviewer reports are in, the editor has to weigh their recommendations. The final decision, however, belongs to the editor alone. They synthesize the feedback with their own expert judgment to determine the paper's fate.

There are usually three possible outcomes at this point:

- Accept: This is the dream, but it's pretty rare on the first try. It means the paper is good to go, maybe with some minor copyediting.

- Revise and Resubmit: This is the most common result. The author gets a chance to improve the paper based on the feedback. The required changes can be minor (like clarifying a few points) or major (like running new analyses).

- Reject: The paper isn't a good fit for the journal. This could be due to fundamental flaws in the research or because it doesn't offer a significant enough contribution to the field.

If a revision is requested, the author has to address every single comment in a response letter and then submit the updated manuscript. Often, this revised version goes back to the original reviewers for a final check before the editor makes their ultimate decision.

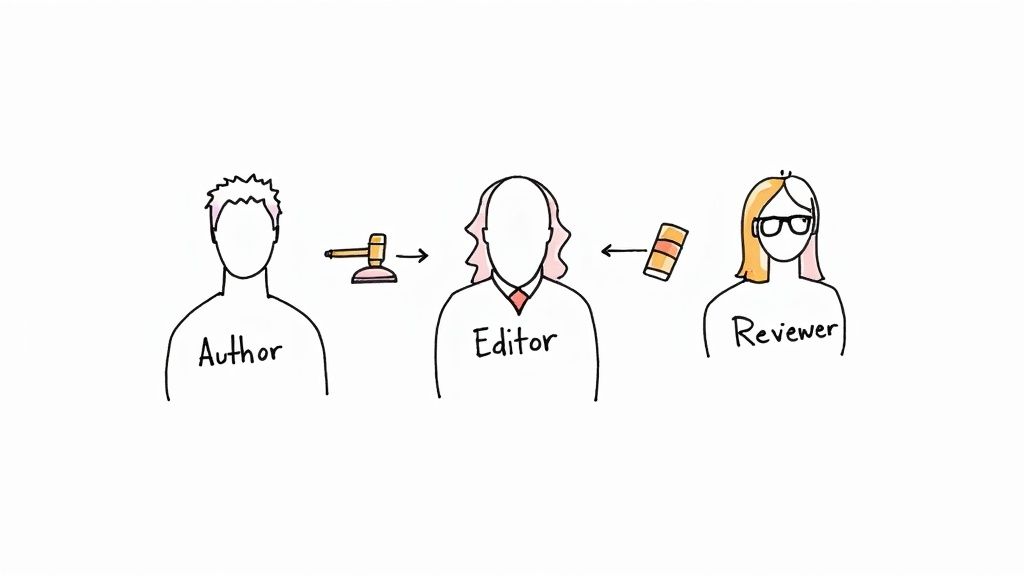

Understanding the Key Roles and Responsibilities

The peer review process isn't a solo performance; it’s more like a carefully choreographed dance. It depends entirely on three key players, each with a critical part to play: the Author, the Journal Editor, and the Peer Reviewers. If you want to understand how scholarly work gets refined and validated, you first have to understand what each of these people does and how they work together.

You can think of these roles as a system of checks and balances for research. The author is the creator, the editor is the project manager and final decision-maker, and the reviewers are the expert consultants brought in for a deep technical analysis. When everyone does their job well, the finished paper is almost always stronger and more credible than the original draft.

The Role of the Author

The author's work starts long before they ever think about clicking "submit." Their main job is to produce research that is original, uses solid methods, and was conducted ethically. This means meticulously following a journal's submission guidelines, writing clearly, and presenting their data and findings with complete honesty.

Once the reviewers' feedback comes in, the author's role shifts. Now, it's about being responsive and professional. They need to thoughtfully consider every single comment—even the ones they might disagree with—and systematically address each point in a revised manuscript, usually accompanied by a detailed letter explaining the changes.

The Role of the Journal Editor

The Journal Editor is the hub of the entire operation. They are the first person to lay eyes on a submitted manuscript and act as the initial gatekeeper. Their first big task is to perform a quick "desk review" to decide if the paper even fits the journal's scope and meets a baseline level of quality. Many papers don't make it past this first step.

If the paper passes this initial screen, the editor moves on to their most crucial responsibility: finding the right peer reviewers. This takes a deep knowledge of the field, as they need to identify experts who can give a fair, rigorous assessment without any conflicts of interest. After the reviews are in, the editor synthesizes the feedback, manages the communication, and ultimately makes the final call on whether to publish.

An editor's role is not just to accept or reject papers. It's to steward the scholarly conversation in their field, ensuring that the work published is not only high-quality but also pushes the discipline forward.

The Role of the Peer Reviewer

Peer reviewers are the unsung heroes of academia. These subject-matter experts volunteer their time to help improve the quality of new research. Their job is to provide a constructive, impartial, and thorough critique of a manuscript. A great review doesn't just point out what's wrong; it offers specific, actionable suggestions on how to make the paper better.

To do their job effectively, a reviewer has to wear several hats:

- Evaluate Originality: Does this research actually bring something new to the table? Is it a significant contribution?

- Scrutinize Methodology: Are the methods sound? Are they described clearly enough that someone else could replicate the study?

- Assess Conclusions: Do the conclusions logically follow from the data presented? Are the claims overblown or well-supported?

- Provide Timely Feedback: Sticking to the journal's deadline is crucial. Delays hold up the entire process for everyone involved.

Each role is a vital piece of the puzzle. The author's diligence, the editor's judgment, and the reviewer's expertise all come together to uphold the integrity of the what is peer review process, making it the cornerstone of academic credibility.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly of Peer Review

Peer review is the gold standard for academic publishing, but let's be honest—it's not a perfect system. It's designed to be a crucial filter that separates rigorous science from flawed or fraudulent work. But since it's a process run by humans, it has some incredible strengths and some persistent, frustrating weaknesses.

On the one hand, its greatest strength is acting as a gatekeeper for quality. Think of it as the first line of defense against pseudoscience and sloppy research. This process ensures that what gets published has, at the very least, met a baseline for sound methodology and logical reasoning. It's this validation that helps us build a trustworthy body of knowledge.

Beyond just filtering, peer review genuinely makes research better. The constructive feedback from experts in the field can be invaluable. It often pushes authors to sharpen their arguments, find stronger evidence, or patch up holes in their logic they might have missed. The end result is almost always a stronger, more polished paper than what was first submitted.

Acknowledging the Systemic Flaws

For all its benefits, the peer review system is creaking under the strain and has some well-known flaws that academics constantly debate.

One of the biggest issues is reviewer bias. Even in a double-blind review where names are hidden, subtle clues about an author’s institution, gender, or theoretical leanings can seep through. Reviewers might unconsciously favor research that confirms their own beliefs or comes from a prestigious university, while unfairly criticizing work that challenges the status quo.

Another massive headache is just how slow the whole process is. Finding qualified reviewers who actually have the time to do a thorough job can take months. Add in a round or two of revisions, and it’s not uncommon for important research to be stuck in publication limbo for over a year. For anyone in a fast-moving field or an early-career academic on a tenure clock, these delays can be brutal.

Peer review is undeniably valuable for validating information credibility—when it works. But the immense strain on the system, with millions of articles submitted annually, means that even a low error rate can result in thousands of flawed articles making it through.

The entire system also runs on the goodwill of experts who are rarely, if ever, paid for their time. Reviewing a paper properly is a serious commitment. Scholars are expected to do this on top of their own research, teaching, and administrative duties. This can lead to reviewer burnout, rushed feedback, and a perpetual shortage of willing experts.

Finally, there's a real risk that peer review can stifle innovation. Reviewers are human, and they can be conservative. They might be more likely to green-light a paper that fits comfortably within existing theories rather than one that proposes something truly radical or groundbreaking. Understanding this is key when you're evaluating research and trying to determine what is a credible source for your own work. These challenges are exactly why the academic community is constantly searching for ways to improve the system.

Common Questions About the Peer Review Process

Even after you've mapped out the steps, the day-to-day reality of peer review can feel a bit mysterious. It's totally normal for authors, especially early in their careers, to have nagging questions about how long things take, what rejection really means, and how to push back on feedback that seems off-base.

Let's pull back the curtain and tackle some of the most common uncertainties researchers run into. Think of this as the practical advice you'd get from a seasoned colleague over coffee.

How Long Does the Peer Review Process Take?

This is the big one, and the honest answer is: it's all over the map. The journey from hitting "submit" to getting a final decision can be as short as a few weeks or stretch out for more than a year. There’s no universal standard.

So, what causes such a huge range? A few key things:

- The Journal's Pace: Some journals have incredibly efficient systems and dedicated editorial staff, while others move at a more traditional, slower pace.

- Finding Reviewers: This is often the biggest bottleneck. The editor has to find experts who are not only qualified but also available and free of any conflicts of interest. It’s common for an editor to send out five or more invitations just to secure two reviewers.

- Rounds of Revisions: If your paper is sent back for "major revisions," it essentially re-enters the review queue after you've resubmitted. Each round can add weeks, or more often, months to the timeline.

While everyone hopes for a quick three-month turnaround, it's a lot healthier to mentally budget six to twelve months for the whole process. Patience isn't just a virtue in publishing; it's a necessity.

What Are the Top Reasons a Paper Gets Rejected?

Rejection stings, but it’s a standard part of the academic process. Almost every researcher has a folder of them. Knowing why papers get turned down can help you steer clear of the most common traps.

Most rejections boil down to one of these issues:

- Fatal Flaws in the Method: This is a big one. Maybe the study design was weak, the sample size was too small to support the conclusions, or the statistical analysis was just plain wrong. If the foundation is shaky, the whole paper will be rejected.

- Doesn't Add Anything New: The research might be sound, but if it doesn't offer a meaningful contribution or advance the conversation in the field, reviewers will often pass on it. The "so what?" question has to be answered clearly.

- Wrong Journal: The paper is a poor fit for the journal's scope and readership. Submitting a highly specialized niche paper to a broad, generalist journal is a classic recipe for a quick "desk reject."

- Sloppy Presentation: The manuscript is so poorly written, structured, or riddled with errors that the reviewers can't even assess the science underneath. A great idea can easily get lost in messy execution.

How Do I Respond to Reviewer Comments I Disagree With?

It’s bound to happen: you get a review back and feel a surge of frustration because a reviewer completely misunderstood your point. The temptation to fire back a defensive email is real, but how you handle this moment is crucial.

The golden rule is to be professional, respectful, and let your evidence do the talking.

Never, ever ignore a comment. In your response letter to the editor, you need to address every single point the reviewers made. If you believe a reviewer is mistaken, explain your position calmly and clearly. Back it up with data from your study or cite established literature that supports your argument. Frame it as a clarification ("Thank you for this point. It seems our original phrasing was unclear...") rather than a confrontation. Your job is to convince the editor your work is solid, not to win a debate with the reviewer.

Finding, managing, and citing your sources shouldn't slow you down. Eagle Cite is an AI-powered citation manager designed to help researchers accelerate discovery and streamline their workflow. Upload papers, highlight key passages, and use natural-language search to find exactly what you need, when you need it. Start your free 14-day trial and spend more time on what matters—your research. Learn more at the Eagle Cite website.